|

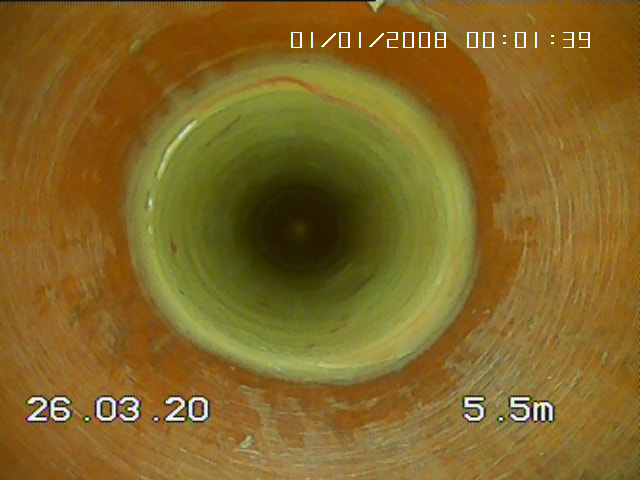

This post is meant to educate both the new CIPP installer and homeowner alike. Unfortunately, many folks are jumping into the trenchless waters with no formal training, no experience, and limited knowledge. As a result, many of the performed repairs are substandard, causing immediate failure or failing prematurely. There are many types of no-dig drain repairs each with it's own specific materials and methods of installation. We will give a brief but in-depth overview of those methods so hopefully you'll be able to recognize some red flags if improper work is being carried out. And if you're new to the trenchless world, or interested in learning more, this article is for you as well. We are going to discuss three types of trenchless repairs (there are more but these are the most common here in Israel): point repair patches, liners, and brush or spray epoxy coating. Let's start with Cured In Place Pipe (CIPP) patches as these are the most common repairs that most homeowners will encounter. The length of the typical repair is 30-60 centimeters although infrequently can be as long as 5 meters in length. A CIPP patch is installed when a specific issue is located in an otherwise healthy drain. Examples: someone drilled a hole into a pipe, roots penetrated a connection or a connection separated (or was not connected properly to begin with). Within the genre of CIPP point repairs there are several subsets: a straight repair, a repair of a 90 degree connection (or several), or a T or wye repair. Each of these repairs require different tools and material. Let's discuss material usage. A repair is made by inserting a flexible sleeve impregnated with a resin that will harden in place. Exactly how the repair is carried out is difficult to explain in words so feel free to watch this video we prepared: The strongest no-dig repair you can make is combining a special fiberglass sleeve with a silicate resin. If done correctly this repair is engineered to last half a century. This leads us to your first red flag. I'm shocked to see, time and time again, installers inserting only 1 layer of fiberglass. That is not how it's done. The fiberglass matt needs to be layered. With Sanikom's 1,050 gram fiberglass matt (I use them as an example as we use their fiberglass matts) the company recommends a double fold for non-structural repairs (for instance repairing a small hole drilled into a pipe) and a triple fold for structural repairs (for instance, penetrating roots or a detached pipe). There are situations where an engineer may request even more layers but in no circumstance is a 1 layer repair considered an acceptable repair. We want this repair to be waterproof, structurally sound and last for decades. The second red flag is an improper pairing of material type and resin type. I've seen folks use a non-fiberglass sleeve (we'll get to that in the lining section) impregnated with silicate resin. This is wholly unacceptable. E-mail or phone any of the major manufacturers and you'll probably get them into cardiac arrest. So, on second thought, you probably shouldn't do that or you'll have something heavy weighing on your conscious. Now why, pray tell, would they do this, you ask. There are two reasons. First reason is that some people find it easier to use the sleeves than the matts. The second reason is that for 90 degree repairs you need a more flexible material for a uniform repair. Now let's discuss the issue with this improper shidduch. The fiberglass matt is considered a structural material that is given form via the silicate resin. The silicate, by itself, is rather weak. The pipe liner, on the other hand, has no structural integrity. It gets it's form and integrity via the epoxy resin. I will repeat: the epoxy resin gives it structural integrity. When you combine silicate with the liner sleeve you get a very week repair. It can detach from the host pipe or the diameter can slightly shrink. Now don't be fooled. The installer may say he is using epoxy, but is he? We often equate confidence with being right, but when armed with the correct knowledge you won't be fooled. So how do you know what resin he is using? First, you can look what is written on the cans. It should say whether it is epoxy or silicate. Next, silicate is usually measured by volume (the silicate resin with the hardener) while epoxy is weighed (the epoxy resin with hardener). There are many different style carriers used to insert these sleeves. There are straight packers (the name for the carrier) for straight repairs, bendy packers for 90 degree bends (some are made for repairing one 90 degree bend while others can take on multiple bends) and special T or wye packers that take a greater degree of craftmanship to correctly perform the repair. I won't go into more depth regarding the different packers except for one point. Inflation pressure. It is extremely important to get the correct inflation pressure so the sleeve forms properly to the pipe. Many people don't realize this but silicate and epoxy are not glues. The point of a CIPP repair is not to glue a new sleeve within the host pipe but to create such a close bond that water cannot penetrate between the two surfaces. Without proper inflation a proper seal will not be created and can result in failure of the CIPP repair. A general rule is that minimum inflation pressure must be 0.3 bar beyond the point where the packer touches the pipe walls. For example, as you increase the pressure inside the packer via an air compressor the packer expands. If the packer uniformly expands to the host pipe at 1.7 bar you'll need to add an additional 0.3 bar to really compress the sleeve to the host pipe for a proper repair (for most repairs we go well beyond this minimum pressure). Let us move on to brush/spray epoxy coating. This is the new hot item in Israel as it's less nerve-wracking than pipe patching/lining (easier to install) and can be applied in places were pipe patching would be difficult to get to. The issue is that many people are using a method that is intended for a specific purpose and broadening it's use for situations that will result in near certain failure. As one leader in the industry told me several times: "when you can line it, you line it; if you can't, you coat it". Why? Because CIPP patches and liners give you a structural repair while coating does not. Coating is mainly designed to elongate the life of failing cast iron piping and metal pressure piping. Coating is not meant to stop root penetrating. The installer also has to be extremely careful to have a 100% dry pipe and let each layer cure before adding the next layer (in general you want to have 3-4 layers, sometimes more, depending on the application). Any movement in the pipe can compromise the integrity of the finished coating whereas CIPP patches and lined pipes are much more forgiving to stressors on the pipe. So when deciding to go with brush/spray epoxy coating understand from the installer why he isn't suggesting patching or lining. Ask him what warranty he is giving and what it covers. Ask him how many layers he will be applying. Ensure that the pipe is 100% dry before the coating process begins. And lastly, ensure that a structural repair is not needed (i.e. to fix a dislocated pipe, root penetration, etc.). (I want to clarify. Every process has it's place. I'm not knocking brush/epoxy coating as a process. I am simply skeptical of its overuse especially when other, better options are unavailable. Secondly, brush/epoxy coating has a far shorter history than patching and lining and thus we have a far less track record of it's durability. When performing a repair I want to know that I am offering our clients the best option and not simply the most convenient option. I have found that many installers don't give options to their clients. To a hammer, everything is a nail. But it may be in your clients interests to open the floor or wall and repair the pipe the "old-school" way if that will guarantee a decades long repair.) Let's move on to lining. Lining is typically done in situations where long, continual sections of pipe needs to be repaired or patching with a packer is technically challenging. Lining is a great solution for failing cast iron or concrete piping. Liners are installed, generally, with inversion drums rather than pushed or pulled in place like in patching. Lining is a world in it of itself so I think it's better that we end here for the time being and perhaps we'll revisit lining in a different article. I would like to leave off with one more piece of advice. A final video inspection of the repair is absolutely critical. You want to ensure that the repair came out uniform, with no significant diameter change in any section of the piping, and that the transition to the host pipe is almost seamless. You should not see any space between the sleeve and the host pipe. As always, if you have any questions or comments feel free to comment below or shoot me an e-mail.

All the best, Yaacov

4 Comments

|

Details

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed